In Part 2 of my talk, I explained that the most range-restricted orchid species tend to be clustered together in very special microhabitats. Identifying and protecting these special microhabitats is the key to preserving the orchid diversity of Ecuador.

On the east slope of the Andes these special microhabitats are often found at middle elevations beginning around 1700-1800m. Unfortunately in Ecuador, as in most other countries including the US, national parks tend to be placed in land that nobody wants, at higher elevations. Middle elevations are valuable for timber and for crops like naranjillo (a tomato relative). This means many centers of orchid endemism lie outside national parks, even in areas where there are a lot of national parks, as in our Banos area.

Our EcoMinga reserves extend protection to the richer lower-elevation forests lying outside the high-elevation national parks.

This is where private foundations like EcoMinga can play a key role. Besides us, there are many other foundations with one or more strategically-located reserves that protect endangered species that are not otherwise protected in national parks. One the best is the Fundacion Jocotoco, which concentrates on protecting endemic bird habitat, but whose reserves also protect extraordinary numbers of endemic plant species. Other foundations that do this include the Jatun Sacha Foundation, Tercer Millenium, Pahuma, Jama, Maquipucuna, and many others. Together we work to create a web of protected areas that fill the gaps between the national parks. The web is currently thin, with many gaps, because funding is scarce. But we are making progress.

Almost all georeferenced collections of endemic plants were made within 750m of a road! Map by Lorena Endara.

One of the limiting factors in weaving this protective web is knowledge. Finding important areas of high local endemism requires hard field work. Sadly, most botanical fieldwork is limited to the immediate vicinity of roads, as shown by this map (made by Lorena Endara) of all the georeferenced collections of endemic plants collected in Ecuador, superimposed on a map of roads. Almost all collections were made within 750m of a road!

Where should we look for new centers of endemism? The front ranges on both the west and east sides of the Andes are the most promising places; their ridgetops are at the optimal elevations for endemic orchids. Isolated mountains farther from the Andes often generate cloud layers at lower elevations than those generated by the Andes, and these are excellent candidates.

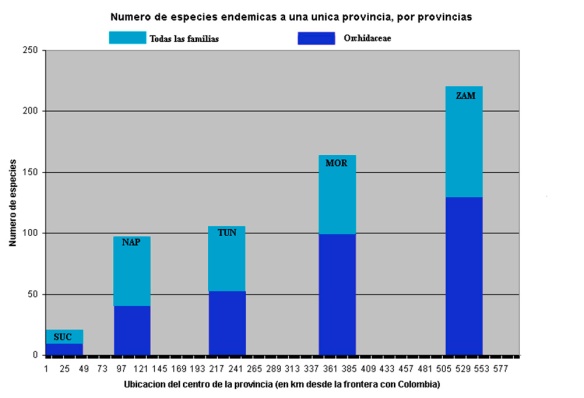

Number of endemic species on the east slope of the Andes, by province bands from north to south. There is a striking linear trend of increasing endemism southward.

I’ve done an analysis of the distribution of endemic orchids and other plants on the east slope of the Andes in Ecuador, using east-west province bands as the geographic units. These bands vary in width, but each band had (at that time) only one major road passing through the Andes into the lowlands, and so I think they are more or less comparable. One might expect the bands near the largest Andean city, Quito, to have more endemic species because of more intense collecting there, but this was not the case. The pattern revealed by the graph is remarkably orderly, with a strong trend of linearly increasing endemism from north to south. The trend is exactly the same for orchids and for non-orchids, which is surprising. Geological substrates are more diverse in the south, and this might explain the increase in endemism of terrestrial plants from north to south. Orchids, however, are primarily epiphytes and not so sensitive to geological substrate. Yet they increase at the same rate as other plants.

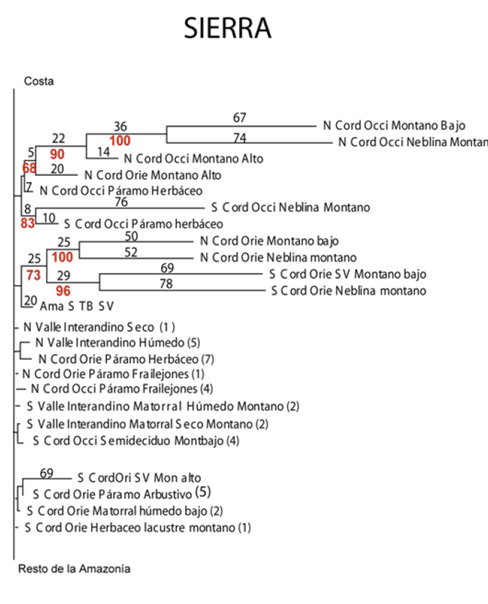

Lorena Endara has done a study trying to pinpoint forest types and regions with higher orchid endemism. In the following graphic, longer branches indicate more endemic species. According to this analysis, the most promising habitats for endemic orchids are the cloud forests of the northwestern Andes (1800-2800m) closely followed by the lower montane forests of the northwestern Andes (1300-1800m). The next most important are the same two forest types in the southeast Andes.

Precipitacion map of Ecuador. Note area of high precipitacion (click to enlarge) circled in northwestern Ecuador. Map: Lou Jost

The northwest Andean cloud forests close to the Colombian border have very high rainfall and might be expected to have especially high orchid diversity. Recent field work has confirmed this, with many new species described from the new road crossing the region from Chical, and others still awaiting description. The northwest is also an area of high deforestation, and the unusually wet habitat types along the upper parts of the Chical road are not known to be represented in national protected areas, making them a very high conservation priority. So when the botanical gardens of the University of Basel asked us to start a reserve there, and offered to help fund it, we accepted the challenge. The Rainforest Trust, the Orchid Conservation Alliance, the Quito Orchid Society, and individual donors enthusiastically joined the project. We have now purchased many key elements of the habitat mosaic in this area, and named it the “Dracula Reserve” in honor of the orchid genus Dracula, which is especially rich there.

Just this week we have signed the deeds which add a new block of forest to our mosaic there, adjacent to the site I wrote about here. We will continue to expand this if funding can be found. This is one of the most diverse and least known areas of Ecuador, and we are excited to be able to protect it!

In Part 4, which I didn’t get to talk about at Yachay for lack of time, I will suggest some novel ways of quantifying conservation objectives.

Lou Jost

www.loujost.com

Please donate to our efforts if you can!