The Beagle in the Galapagos.

When Charles Darwin first landed on Ecuador’s Galapagos Islands in 1835, he was not impressed:

“The black rocks heated by the rays of the Vertical sun, like a stove, give to the air a close & sultry feeling. The plants also smell unpleasantly. The country was compared to what we might imagine the cultivated parts of the Infernal regions to be… I proceeded to botanize & obtained 10 different flowers; but such insignificant, ugly little flowers…” —Diary

“Nothing could be less inviting than the first appearance. A broken field of black basaltic lava, thrown into the most rugged waves, and crossed by great fissures, is everywhere covered by stunted, sun-burnt brushwood, which shows little signs of life… With the exception of a wren with a fine yellow breast, and of a tyrant-flycatcher with a scarlet tuft and breast, none of the birds are brilliantly coloured….All the plants have a wretched, weedy appearance, and I did not see one beautiful flower. The insects, again, are small-sized and dull-coloured…. I took great pains in collecting the insects, but excepting Tierra del Fuego, I never saw in this respect so poor a country.”—Voyage of the Beagle

Galapagos scene. Photo: Wikipedia Commons

Still, as was his custom, he collected specimens of as many distinct plants and animals as he could. There was as yet no evolutionary insight, just curiosity. He wrote in his diary at the time

“It will be very interesting to find from future comparison to what district or “centre of creation” the organized beings of this archipelago must be attached.”

His first flash of insight about the nature of the Galapagos flora and fauna came after the Beagle had already left the islands to go to Tahiti. During the long travel days with blank seascapes stretching in all directions, he worked on his specimens. It was only then that he noticed something surprising. Ten years later (in his second edition of “Journal of Researches” p. 394) he wrote about that moment on the Beagle:

“My attention was first thoroughly aroused, by comparing together the numerous specimens, shot by myself and several other parties on board, of the mocking-thrushes [mockingbirds], when, to my astonishment, I discovered that all those from Charles Island belonged to one species (Mimus trifasciatus); all from Albemarle Island to M. parvulus; and all from James and Chatham Islands (between which two other islands are situated, as connecting links) belonged to M. melanotis. These two latter species are closely allied, and would by some ornithologists be considered as only well-marked races or varieties; but the Mimus trifasciatus is very distinct. Unfortunately most of the specimens of the finch tribe were mingled together…”

“This bird which is so closely allied to the Thenca [mockingbirds] of Chili … is singular from existing as varieties or distinct species in the different islands.

“…I never dreamed that islands about 50 or 60 miles apart, and most of them in sight of each other, formed of precisely the same rocks, placed under a quite similar climate, rising to a nearly equal height, would have been differently tenanted ….”

“It is the fate of most voyagers, no sooner to discover what is most interesting in any locality, than they are hurried from it; but I ought, perhaps, to be thankful that I obtained sufficient materials to establish this most remarkable fact in the distribution of organic beings.”—-Zoology notes p. 298

Gould’s plate of Darwin’s Finches. Creative Commons

When he eventually returned to England, he gave his plant and animal specimens to specialists who could distinguish which ones were new species, and could figure out how they were related to each other. The great ornithologist Gould was the first to finish this task. His report to Darwin was quite a shock. Darwin had rather casually collected many dingy birds on the Galapagos. As he mentions in the excerpt above, he didn’t even bother to label some of them with the names of the specific islands where they had been collected. (Luckily some of his shipmates did make properly-labeled specimens, so their distributions were eventually sorted out.) He thought some of these dingy birds were finches, some were warblers, some were wrens, and some were blackbirds (icterids). Ornithology was not one of Darwin’s strong points. (He once ate an important new species of rhea before realizing that it was the bird he had long been searching for!) Gould, however, was a good ornithologist, and recognized that all these different birds actually belonged to twelve closely-related species of a single subfamily, not found anywhere else in the world at the time, known today as Darwin’s finches (later one additional species was discovered on Cocos Island off Costa Rica). This was an astonishing discovery, that birds with such outwardly-different beaks and habits would all be so closely related, and that there would be different sets of them on different islands.

Leaf shapes of different species of Scalesia . From U. Eliasson (1974) Studies in Galápagos Plants. XIv. The Genus Scalesia Arn. Opera Botanica 36: 1–117, under Fair Use.

The same turned out to be true of Darwin’s Galapagos plants, which he had first given to his old teacher Henslow and then to his close friend Hooker. Hooker discovered that many of Darwin’s plants belonged to a single genus, Scalesia, found nowhere else in the world. Just like the birds, there were different species of Scalesia on different islands. Darwin wrote:

“Scalesia, a remarkable arborescent genus of the Compositae, is confined to the archipelago: it has six species: one from Chatham, one from Albemarle, one from Charles Island, two from James Island, and the sixth from one of the three latter islands, but it is not known from which: not one of these six species grows on any two islands.”

“The distribution of the tenants of this archipelago would not be nearly so wonderful, if, for instance, one island had a mocking-thrush, and a second island some other quite distinct genus, — if one island had its genus of lizard, and a second island another distinct genus, or none whatever; — or if the different islands were inhabited, not by representative species of the same genera of plants, but by totally different genera, as does to a certain extent hold good: for, to give one instance, a large berry-bearing tree at James Island has no representative species in Charles Island. But it is the circumstance, that several of the islands possess their own species of the tortoise, mocking-thrush, finches, and numerous plants, these species having the same general habits, occupying analogous situations, and obviously filling the same place in the natural economy of this archipelago, that strikes me with wonder.”

“Although the species are thus peculiar to the archipelago, yet nearly all in their general structure, habits, colour of feathers, and even tone of voice, are strictly American.”

“… Hence, both in space and time, we seem to be brought somewhat near to that great fact – that mystery of mysteries – the first appearance of new beings on this earth…..one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends…..”

These patterns, which would now call “evolutionary radiations”, were some of the most important clues in Darwin’s intellectual journey towards his theory of evolution. In 1837 he wrote in a private notebook:

“In July opened first note-book on ‘transmutation of species.’ Had been greatly struck from about month of previous March on character of South American fossils, and species on Galapagos Archipelago. These facts origin (especially latter), of all my views.”

The plant and animal radiations on the Galapagos Islands went on to become icons of evolutionary theory. Later explorers pushed the number of species of Darwin’s finches to about fourteen. New Scalesia species continued to be discovered until as recently as 1986, pushing the total Scalesia species to fifteen, with up to four species on a single island. The total number of plants that are unique to the Galapagos Islands, and not found anywhere else in the world, is now about 175-180 species. Because of its immense scientific importance it was made a national park by the Ecuadorian government and declared a World Heritage site by the UN.

Even today, seeing these kinds of evolutionary radiations leaves one with a palpable sense of direct contact with Darwin’s “mystery of mysteries”, the evolution of new species. I got my first taste of this feeling in the Ecuadorian Andes around Banos twenty years ago, as I explored the mountains of the upper Rio Pastaza watershed looking for new orchid species.

The upper Rio Pastaza watershed. Photos: Andreas Kay.

Evolutionary radiation of Lepanthes orchids in the upper Rio Pastaza watershed. Left: a widespread species, L. mucronata. Middle and right: two new species I discovered here, closely related to L. mucronata. These are L. abitaguae (middle) and L. pseudomucronata (right). Photo: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

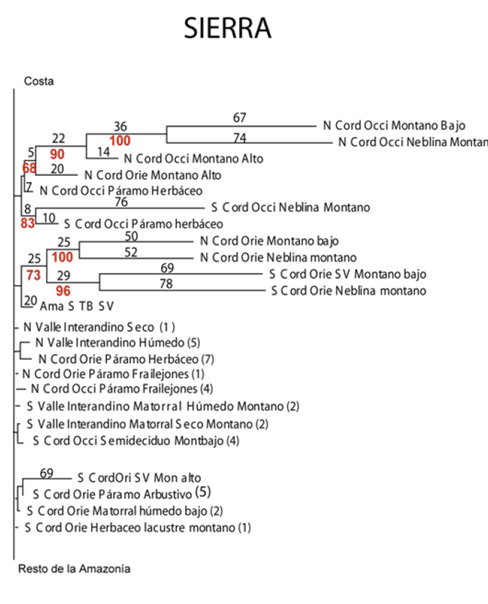

At first I discovered lots of little radiations, mostly in the orchid genus Lepanthes–two or three new closely related species, sometimes different “sister species” on each mountain, as if these mountains were acting like islands in the clouds. In other cases, I found sets of closely-related new species all living together on a single mountain, analogous to the multiple species of Scalesia that lived on some individual Galapagos islands. Slowly, over the years of hiking, patterns began to emerge from the maps I made of the distributions of these species. It was like watching the construction of a stained-glass window, each beautiful fragment adding more detail until order began to triumph over chaos.

Cerro Mayordomo. Photo: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

Then in the year 2000 everything changed. After a year of failed attempts, I finally figured out how to get up a high unexplored mountain between Banos and Puyo. It was called “Mayordomo” on the maps. After two day’s climb, I reached a beautiful mossy cloud forest at 3100m. I looked down and at my feet I saw little orchid plants creeping through the thick moss, with single leaves widely spaced on a thin stem. I began to find a few with flowers, but still I had no idea what they were. I couldn’t even recognize their genus –quite embarrassing for me, who claimed to be an orchid expert! The strangest thing was that there were four clearly-different species of these strange creeping orchids right here in one square meter of moss. How could such a big group of species be unfamiliar to me?

Mysterious Teagueia orchids creeping through moss on Cerro Mayordomo. Photo: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

I could hardly wait to get home and look them up in books. But there was nothing like them in any book. I sent them to the world’s specialist in miniature orchids, Carl Luer, and he wrote back excitedly that these were all new to science, and belonged to a tiny genus of orchids called Teagueia. Up until that moment, there had been only six species of Teagueia known in the whole world, three from Ecuador and three more from Colombia, all very local endemics. In my one square meter of moss I had more than doubled the number of species of Teagueia in Ecuador. Most interesting was that all of my new species were long-stemmed creeping plants, unlike any of the previously-known Teagueia species. The new species also shared floral traits not found in any of the previously-known species. Such clues suggested that these new species had evolved right here, from a recent common ancestor, just like Darwin’s finches or his Scalesia plants in the Galapagos. Carl quickly described the new species: Teagueia sancheziae (after my friend Carmen Sanchez who climbed the mountain with me), T. alyssana (after my dear friend Alyssa Roberts who helped support my research), T. cymbisepala (a Greek word referring to the shape of the flower), and T. jostii, which Carl decided to name after me.

Teagueia alyssana, one of the new Teagueia species I discovered on Cerro Mayordomo. Photo: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

The discovery of this evolutionary radiation raised an obvious question: How many more of these species might be hidden on this and the many other unexplored mountaintops around my town of Banos? I eventually returned to Mayordomo and got higher up the mountain on a long camping trip with my hiking companions Robert and Daisy Kunstaetter. There was no rain during the whole trip, so we had to use rainwater I had collected and stored in a big plastic bag at an old campsite of mine several years earlier. It was still good, thanks to a few drops of iodine I had added when I stored it. When that ran out we were forced to squeeze dew out of moss; this was horrible, though I discovered a new Maxillaria orchid while collecting the moss. We had to abort the trip early, but we still managed to find three or four more new Teagueia species! All had long creeping stems and shared floral characteristics with my previous discoveries. This unexpected evolutionary radiation of plant species was turning out to be bigger than I could have imagined.

Some Mayordomo Teagueia species. Photos: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

A year or so later, Robert and Daisy came back from the next mountain to the west of Mayordomo with an interesting leaf to show me. They thought it might be from a Lepanthes, but it was another of these creeping Teagueia species! I went up that mountain and found it covered with creeping species of Teagueia. Some were the same species as on Mayordomo, but many of them new to science. All of these new one were clearly related to the ones on Mayordomo.

One of the new Teagueia species I discovered on the mountain just west of Cerro Mayordomo. Photo: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

Unexplored mountains south of the Rio Pastaza. Photo: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

Did every mountain around here have its own new species of Teagueia? I sometimes give a guest lecture to visiting biology students at the School for International Training, in Quito the capital of Ecuador. After I talked about these Teagueias, two students, Pailin Wedel and Anderson Shepard, volunteered to do an independent study project on the genus. They wanted a challenging project, so I trained them to recognize Teagueia plants (Andy discovered a fantastic new Teagueia on one of his training trips!) and then I sent them off with a local guide for a week to look for Teagueia on a mountain south of the Rio Pastaza that I had never explored. Andy was a mountain rescue guide from Colorado so I figured they’d be alright. The deep valley of the Rio Pastaza separated this mountain from both Mayordomo and my other Teagueia mountain, so none of us knew what to expect.

The students survived, though they said it was the hardest thing they had ever done, and Pailin lost a toenail from the long muddy climb. They didn’t mind; they had found eight or nine species of creeping Teagueia, each new to science! None of the species on their mountain were shared with the two mountains on the other side of the Rio Pastaza valley. This was unexpected, since the other orchids I had studied showed a different distribution pattern.

A new Teagueia discovered by Andy and Pailin. I’ll name this one after Pailin. Photo: Andreas Kay.

Another new Teagueia discovered by Andy and Pailin. I’ll name this one after their local guide Ali Araujo. Photo: Andreas Kay.

There was still one more big unexplored mountain between Banos and the Amazon lowlands, known on the maps as Cerro Candelaria. It rose to 3860m, much higher than the other mountains we had looked at. It was like a magnet. My friends the Kunstaetters and I finally climbed all the way to the top at the end of 2002. It was a difficult nine day camping trip, eased somewhat by the help of some local people (who later became EcoMinga’s forest guards) whom we hired to carry our packs the first (and steepest) day. This mountain not only had all the new Teagueia species my students had found on their mountain, but also another six Teagueia species that were completely new! For a magnificent photographic album of Cerro Candelaria, including many Teagueia species, see Andreas Kay’s Cerro Candelaria Flickr album.Highly recommended!

Some of the new creeping Teagueia species discovered by my students and I in the upper Rio Pastaza watershed. All flowers are photographed at the same magnification so relative sizes are accurately shown. Click to enlarge! Photos: Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

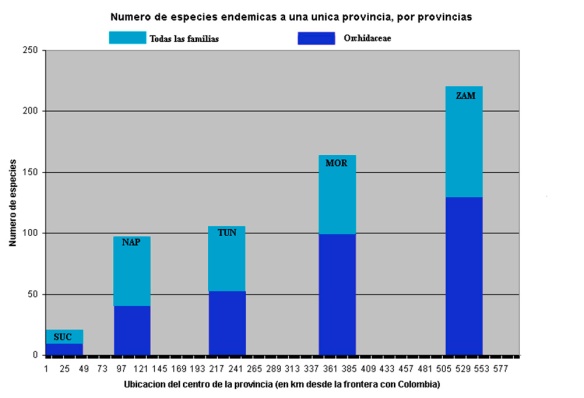

As a result of these expeditions, we now know that this evolutionary radiation of Teagueia species contains almost double the number of species of the famous Galapagos radiations, even though the Galapagos islands are much bigger and more numerous than these four mountains, and even though geographic isolation here is much less complete than in the Galapagos. And unlike any island in the Galapagos, a single mountain here can have 8-15 Teagueia species growing together. (In a future post I’ll write about what DNA analysis tells us regarding the speed of this evolutionary radiation relative to that of the Galapagos Scalesia radiation.) Counting these new Teagueia species, there are now about 190 unique endemic plant species in our upper Rio Pastaza watershed. That is more locally endemic species than there are in all of the Galapagos. This is a region that has much to tell us about the mysteries of speciation, maybe even more than the Galapagos.

Teagueia distribution in the upper Rio Pastaza watershed. Lou Jost/EcoMinga.

Conservation can have many motives, but one of mine is to preserve enough of the earth’s legacy that future generations will still be able to unravel those fundamental mysteries that we have not yet been able to figure out. The answer to the question of the origin of species is written here in these mountains, but we are tearing up the pages before we have learned how to read them. One of the reasons my friends and I founded EcoMinga was to save some of those pages, hopefully the most strategic ones. Thanks to our partner the World Land Trust, we have now bought the mountain that has sixteen species of Teagueia; it also turns out to have many other unique newly-discovered species of orchids, trees, frogs, and more. Thanks to them and many other donors (Rainforest Trust, Orchid Conservation Alliance, University of Basel Botanical Garden, Montreal Botanical Garden, and some generous individual donors to EcoMinga) we have also begun to buy land on Mayordomo, and other places where unusual evolutionary forces have led to high concentrations of new, locally endemic species of plants and animals. Not only do we want to preserve the biodiversity of these places, we also want to preserve the clues they contain to the origin of biodiversity itself.

Can’t have a Darwin Day post without including a picture taken by our own Darwin Recalde. Darwin is Jesus Recalde’s son and a great young naturalist. Here he has managed to photograph an elusive Rufous Antpitta standing on a bunch of Teagueia. Photo: Darwin Recalde/EcoMinga.

Lou Jost