Pacarana (Dinomys branickii). Photo: Wikipedia.

Traduccion en espanol abajo]

Surely the strangest animal of our new Manduriacu Reserve is the Pacarana (Dinomys branickii), the world’s third-largest rodent in terms of length (after the capybara and the beaver). It is almost a meter long and weighs up to 15 kg (more than 30 lbs). It is a rare, slow-moving nocturnal animal whose natural history was until very recently almost completely unknown. None of us has ever seen it, but several grainy infrared images captured by Sebastian’s camera traps prove its presence in Manduriacu.

Pacarana (Dinomys branickii) captured at night by Sebastian’s infrared camera trap.

It was first discovered in Peru in 1873, and immediately recognized as belonging to a new family of mammals never seen before. It had many odd features, such as four-toed paws rather than the usual five. No more individuals reached the scientific community (though surely many reached the cooking pots of local campesinos) until 1904, when a captive pair was given to a Brazilian zoo. In 1921 the first pacarana from Colombia was found and described as a distinct species (D. gigas); later, once the variation within populations was better understood, this form was lumped with the original D. branickii.

Captive animals turned out to be tame and affectionate. Karl Shuker notes that “…They actively seek out their human visitors to nuzzle them and rub themselves against their legs almost like cats, or even to be picked up and carried just like playful puppies.”

Nevertheless the scientific name of the genus comes from one of the same Greek words as the term “dinosaur”, which means “terrible (or terrifying) lizard”. “Dinomys” literally means “terrible mouse”! Before you laugh at this apparent oxymoron, though, let’s get some historical perspective on this guy’s relatives. Dinomys branickii is the sole survivor of an ancient and once very diverse family of South American rodents, the Dinomyidae, which split off from other rodent families about 17-21 million years ago. The family descended from a caviomorph rodent which probably drifted to South America from Africa 40 million years ago. (It is thought that the ancestor of all South American monkeys arrived from Africa the same way, at around the same time.) When these ancestral rodents got to South America, they found an island continent with many unfilled or inefficiently-filled ecological niches. They diversified to fill these niches, apparently out-competing many weird endemic South American mammals. They eventually evolved into several different rodent familes, including the Dinomyidae.

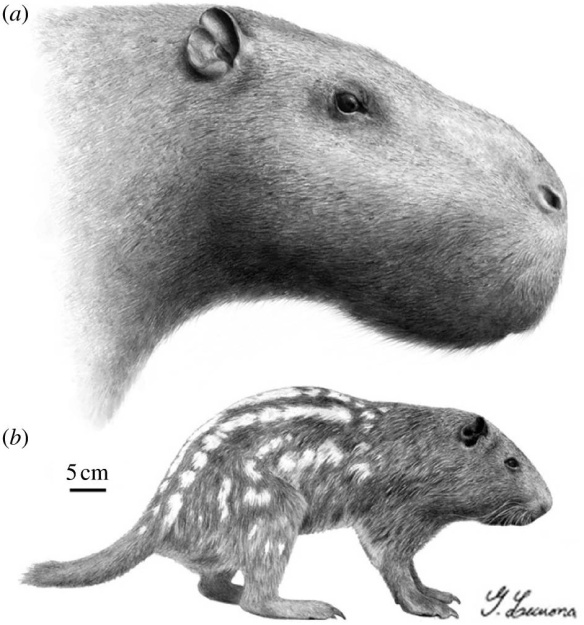

The living Pacarana (Dinomys branickii, below) and its extinct relative, Josephoartigasia monesi. Figure 3 from Rinderknecht and Blanco (2008).

As the Dinomyidae diversified into new ecological niches, they also diversified in body size. The smallest of the fifty known fossil Dinomyidae species, Myoprocta, had a mass of only 1 kg. But most of the diversification wasa towards larger body sizes. Some of these “mice” had body sizes approaching those of hippopotamus, rhinoceros, and buffalo!!! “Terrible mouse” indeed! The largest Dinomyid, Josephoartigasia monesi, weighed about 1000 kg (one ton), the largest rodent that ever lived. Its front incisors were disproportionately huge, and may have been used to dig, or to fight. South America was full of buffalo-sized rats until continental drift linked it to Central America, introducing new forms that could in turn out-compete or eat these giants, just as the Dinomyids had outcompeted many of the earlier South American endemic mammals. The same wave of Central American newcomers (eventually including humans) also eliminated the giant ground sloths and many other strange endemic South American mammals and birds, probably helped along by a change to a drier climate.

As the Pleistocene ended, the only Dinomyid that survived all these changes was our unassuming Pacarana. It still has a large range, mostly on the eastern slopes of the Andes and adjacent Amazonia, with a narrow almost-disjunct population in the foothills on the west side of the Andes (where Manduriacu is located). Limited gene flow between the west and east populations, coupled with the different selective pressures on each side, may have led to genetic differentiation between them, but this has not yet been studied.

Pacarana range map, from IUCN Red List (http://maps.iucnredlist.org/map.html?id=6608)

Even though the range is large, individuals are seldom seen, and they are hunted intensely for their meat. Their rate of reproduction is very slow compared to that of other rodents: its gestation period is 220-280 days, and it only bears one or two young at a time. This slow rate of reproduction means that even very light hunting pressure will exterminate it from an area.

Jorge Brito, expert in Ecuadorian mammals, reports that he once found a hunter with a Pacarana carcass in what is now our Dracula Reserve in western Ecuador near the Colombian border, so these animals once existed there. We have no evidence of their continued presence, though they might still be there somewhere. We have also not seen any Pacarana in our extensive camera trap surveys of our upper Rio Pastaza reserves, though Jorge Brito once caught a glimpse of one in nearby Parque Nacional Sangay. That is the only individual that Jorge ever saw, so this is a very rare and/or hard-to-detect mammal. Undoubtedly it has been eliminated near human settlements.

It may be useful to look for the animal’s scat and foraging damage. A study in Colombia by Carlos A. Saavedra-Rodríguez1, Gustavo H. Kattan, Karin Osbahr, and Juan Guillermo Hoyos (2012), Multiscale patterns of habitat and space use by the pacarana Dinomys branickii: factors limiting its distribution and abundance, in the journal Endangered Species Research vol 16:273–281, Supplementary Material, contains photos of these signs of Pacarana presence:

<img src=”https://ecomingafoundation.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/supp1.jpg” alt=”Pacarana foraging marks. From Supplementary Material, Carlos A. Saavedra-Rodríguez1, Gustavo H. Kattan, Karin Osbahr, and Juan Guillermo Hoyos (2012), Multiscale patterns of habitat and space use by the pacarana Dinomys branickii: factors limiting its distribution and abundance, in the journal Endangered Species Research, vol 16:273–281. Fair Use license. ” width=”584″ height=”373″ class=”size-full wp-image-2220″ /> Pacarana foraging marks. From Supplementary Material, Carlos A. Saavedra-Rodríguez1, Gustavo H. Kattan, Karin Osbahr, and Juan Guillermo Hoyos (2012), Multiscale patterns of habitat and space use by the pacarana Dinomys branickii: factors limiting its distribution and abundance, in the journal Endangered Species Research, vol 16:273–281. Fair Use license.

Pacarana dried droppings. Ruler is in cm. From Supplementary Material, Carlos A. Saavedra-Rodríguez1, Gustavo H. Kattan, Karin Osbahr, and Juan Guillermo Hoyos (2012), Multiscale patterns of habitat and space use by the pacarana Dinomys branickii: factors limiting its distribution and abundance, in the journal Endangered Species Research, vol 16:273–281. Fair Use license.

Since conservation resources are limited, global resource managers must always think carefully about which animals and ecosystems they should protect. One important criterion for protection is “evolutionary distinctiveness”. An animal that has no close living relatives carries many genes that are not found in any other animals, and may have unique biochemical and ecological traits, so it should have a higher conservation value than an animal with many close relatives. An ecosystem with such a phylogenetically distinct animal is more valuable than a community with the same number of species but less phylogenetic diversity. (My colleague Anne Chao and I have developed mathematical methods for quantifying the phylogenetic diversity of an ecosystem; see below for citation.) The pacarana, last survivor of the once terrible Dinomyidae, adds much to the conservation value of Manduriacu.

See this site for more information about the living species, and this one for some information about the extinct ones.

For the mathematics of diversity measures that incorporate phylogenetic diversity, see Chao, Chiu, and Jost 2010.

Lou Jost

Fundacion EcoMinga

Pingback: Manduriacu Reserve from the air | Fundacion EcoMinga

Pingback: How to land a fixed-wing drone in a dense forest | Fundacion EcoMinga