Camera trap video by our friends and neighbors at Merazonia

[Traduccion al español abajo]

Neotropical rainforest mammals are notoriously hard to spot in the complex and dense vegetation. Predators are particularly stealthy, and thinly distributed as well. Cats are famous for their invisibility: I’ve only seen a jaguar once in 40 years of tropical fieldwork, and the puma still eludes me even though it is known to exist in nearly every place I have ever been. But the two rainforest dog species, the Bush Dog (Speothos venaticus) and the Short-eared Dog (Atelocyon microtis), reach another level of invisibility; they are almost mythical beasts. Almost no one ever sees them. A testament to the difficulty of spotting one of these is that the Bush Dog was first described by Peter Lund in 1839 from a fossil. Only later did European scientists realize that the ghostly animal still haunted the Amazon forests. Though I did once catch a glimpse of a Short-eared Dog in the Amazon, I have never seen the Bush Dog in the wild, nor has any other local observer. Our local wardens, who are extremely good naturalists, had never even known of its existence.

The actual fossil skull that Peter Lund discovered and used as the basis for his description of Speothos venaticus. Photo: PhD thesis by Kasper Lykke Hansen

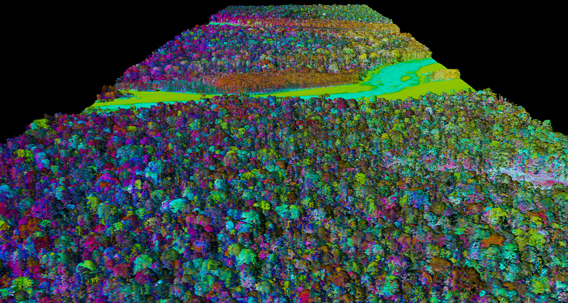

Yet here they were, living unseen in the Rio Anzu watershed, silently going about their business. We had no idea they were here. Finally in 2020 some of them were caught by an automated camera trap of the wildlife rescue center, Merazonia, near our Rio Anzu Reserve. This is an extraordinary event in itself, but the camera traps at Merazonia caught them two more times in the same general area during the following two years.They have accumulated about 9000 camera-days to get these three detections, so they have an average of about one detection per 3000 camera-days.

This is typical of Bush Dog detections by camera traps. Bush Dogs everywhere have an extremely low detection rate, much lower than jaguars for example. In the province of Minas Gerais en Brazil, where the Bush Dog was originally discovered by Lund, the species was thought to be extinct for decades, but a footprint was discovered in 2005. This sparked a World Wildlife Fund effort to photograph it with camera traps, but it took seven years of effort to finally photograph one with a camera trap. In Costa Rica, at the northern limit its range, a recent study estimated that it would take 2500 camera-days (number of cameras per day, multiplied by the number of days the cameras were running) to have a 50-50 chance of photographing one. In a large park in southern Costa Rica it took 2376 camera-days to capture two shots (one detection per 1000 camera-days). For comparison, in the same period at that site, about 13 jaguar pictures were made by the same cameras. In the rainforests of Panama, in 32000 camera-trap days only 11 detections of Bush Dogs were made, for a detection rate of one per 3000 camera-days, the same detection rate as at Merazonia.

Bush Dogs often travel in small groups of up to ten animals, and are the most social of all the native Neotropical dog species. They hunt mostly large forest rodents. Both males and females place scent-marks on trees as they move through the forest. With the permission of Frank Weijand, head of Merazonia, I’ve enlarged the Merazonia video and slowed it down to half-speed, so you can see the way that all three individuals (presumably two males and a female) diligently mark the same foreground tree. Note also that one individual has a darker body while the others have rusty coats.

These dogs weigh between 5 and 8 kg (11-18 pounds). Pre-Hispanic Amazonian native people apparently domesticated these Bush Dogs before the introduction of our common domestic dog. Alfred Russell Wallace, describing his personal observations of Amazonian mammals in 1889, mentioned the presence of a “wild dog, or fox, of the forests; it hunts in small packs; it is easily domesticated, but is very scarce.” This probably refers to the Bush Dog since it is the only Amazonian native dog species that hunts in small packs. There are also reports that Bush Dogs may have been raised for food by indigenous people, and perhaps may even have been traded with cultures as far away as the Caribbean islands in pre-Columbian times, though the evidence for this is weak.

However, in the Amazonian villages that I have been able to stay in (belonging to the Kichua, Shuar, and Huaorani cultures), I did not see or hear of any present-day domesticated Bush Dogs (though I did not specifically ask about them either).

It may be difficult for Bush Dogs to co-exist with domestic dogs, because Bush Dogs seem to be very sensitive to diseases hosted by domestic dogs . Given the large populations of feral dogs in many areas, including the Rio Anzu watershed, this is probably the single biggest threat to long-term Bush Dog survival.

Evolutionary history of the Bush Dog

There were no dogs in South America during its “island” days (70 million years ago to about four million years ago). Dogs arrived, along with many other groups (like bears, tapirs, deer, pigs, camelids, pit vipers, and many others), around 3-4 million years ago when a land bridge first connected North and Central America to South America.

Biologists have long assumed that dogs had diversified in North and Central America before the appearance of the land bridge, and that multiple dog lineages then crossed the land bridge into South America and continued to diversify. However, this year (2022) biologists discovered that ALL the South American dog species (Maned Wolf, Short-eared Dog, Bush Dog, Crab-eating Fox, and others) are the result of local diversification in South America from a single common ancestor that crossed the land bridge 3.5-4 million years ago! It demonstrates the evolutionary plasticity of the dog genome and the potential speed of evolution.

These and other earlier results also reveal that the closest relative of the short-legged hyper-carnivoroous Bush Dog is not the other Neotropical rainforest dog, the similar-looking Short-eared Dog (Atelocynus microtis ), as had long been thought, but rather the big long-legged mostly frugivorous Maned Wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus) of the savannahs of southern South America. Appearances can be deceptive!

The Short-eared Dog, Atelocynus microtis, is the only other neotropical rainforest dog beside the Bush Dog. Even though it looks much like the Bush Dog, the Maned Wolf is a much closer relative to the Bush Dog. Appearances can be deceiving. Photo: Igor de le Vingne – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=89380067

The Maned Wolf, Chrysocyon brachyurus, from the savannahs of Brazil and neighboring countries, is the closest living relative to the Bush Dog. Photo: sarefo – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=718357

A note on the Danish paleontologist, zoologist, and archaeologist Peter Lund (1801-1880)

Besides discovering the fossil Bush Dog (see photo above of the very skull that he excavated), Peter Lund is also the first European to find the living Bush Dog, a few years later, but he did not recognize the two animals as the same, and established the genus Icticyon for the living Bush Dog. Since Speothos was published before Icticyon, it has priority by the rules of scientific nomenclature. so we use that name rather than Icticyon.

I think this is the first painting a Bush Dog. It was made by Peter Andreas Brandt in Lagao Santa, MInas Gerais, Brazil, where he was acting as the scientific illustrator for Peter Lund. Lund discovered the first fossil Bush Dog and, shortly after, the first living Bush Dogs. Perhaps these painted individuals were the very ones that Lund used for his scientific description of the live animal.

Lund also discovered fossils of a much bigger and more robust bush dog, Speothos pacivorus, This powerful animal became extinct only about 11000-12000 years ago! The Amazon might have been be a dangerous place for humans when they were around.

An extinct bush dog species, Speothos pacivorus, was a strong and heavily-built animal. It became extinct just 11000-12000 years ago. Photo credit; https://prehistoria.fandom.com/es/wiki/Speothos_pacivorus

Lund spent many years excavating the caves of Minais Gerais. Besides the Bush Dogs he discovered there, he also discovered the famous Sabre-toothed Cat in these caves, and he also found human remains. He was the first scientist to discover that humans lived alongside such extinct animals. At the time, the world’s greatest authorities, such as Cuvier, believed in “catastrophes” which eliminated all species of an epoch, after which the world was repopulated by the creation of a new fauna. This belief is probably what kept Lund from realizing that his fossil Bush Dog Speothos venaticus and his living Bush Dog Ixicyon were the same species. According to the theory of the time, they could not be the same. But eventually his discoveries began to erode these scientific and religious beliefs. Deeply conflicted, he was confused but confident of his conclusions about the coexistence of humans and extinct animals, which was considered impossible by most scientists of the time. He wrote in a letter to a friend:

“On the other hand, I cannot deny that aspects of earlier points, which I believed to have been established, have been covered by new darkness, and what I thought had been clarified has not been fully illuminated. This refers, for example, to the… important issue concerning the circumstances of the succession of ages and the identification of species, and the question not least of the separating line between them. The latter became for me totally obscure. I observe several extinct species, like the ones I discovered, below that line towards the present, and several of the species of the present move over it towards the past. … This year I was lucky to find [human] remains under different conditions, which for me leave no doubt that they have witnessed the end of at least five species of mammals.”—- Peter Lund, as translated from the Portuguese by Google Translate, with some “corrections” (I hope) from me.

Lund was so conflicted by his discoveries that he never returned to his caves. The story is told (in Portuguese) by Pedro Ernesto De Luna Filho (2007), Peter Wilhelm Lund: His scientific investigations and the reason he suddenly stopped his research. The above letter (in Portuguese) is taken from de Luna’s thesis article. I wish I knew Portuguese, though Spanish is almost good enough to understand it.

Lund’s neighborhood in Lagao Santa, Brazil, painted by Peter Brandt around 1840. Lund lived in Brazil until his death in 1880.

Lou Jost, Fundacion EcoMinga

Titulo original: The mysterious Bush Dog (Speothos venaticus)

Link: https://ecomingafoundation.wordpress.com/2022/10/23/the-mysterious-bush-dog-speothos-venaticus/

El misterioso Zorro Vinagre (Speothos venaticus)

VIDEO 01 – Video de cámara trampa hecho por nuestros amigos y vecinos Merazonia

Los mamíferos del bosque lluvioso neotropical son notablemente difíciles de observar en la compleja y densa vegetación. Los depredadores son particularmente cautelosos, así como finamente SINONIMO AQUI distribuidos. Los felinos son famosos por su invisibilidad. Solo he visto un jaguar por única vez, en 40 años de trabajo de campo en los trópicos, y el puma todavía me elude incluso aunque se sabe que se distribuye en casi todo lugar en el que he estado alguna vez. Pero las dos especies de perros de bosque lluvioso, el Zorro Vinagre (Speothos venaticus) y el Zorro de Orejas Cortas (Atelocyon microtis), llegan a otro nivel de invisibilidad; ellos son bestias casi míticas. Casi nadie las ve. Un testimonio de la dificultad de encontrar uno de estos es que el Zorro Vinagre fue descrito por primera vez en 1839, a partir de un fósil. Solo después los científicos europeos descubrieron que el animal fantasmal todavía cazaba en los bosques amazónicos. Aunque una vez alcancé a vislumbrar un Zorro de Orejas Cortas en la Amazonía, nunca había visto el Zorro Vinagre en la naturaleza, ni lo había visto cualquier otro observador local.

IMG 01 – El cráneo fósil que Peter Lund descubrió y utilizó como base para su descripción de Speothos venaticus. Fotografía: Tesis de PhD de Kasper Lykke Hansen.

Sin embargo, aquí están, viviendo sin ser vistos en la cuenca del Río Anzu, ocupándose en silencio de sus asuntos. No teníamos idea de que estaban aquí. Finalmente, en 2020, algunos de ellos fueron captados por una cámara trampa automática del centro de rescate de vida silvestre, Merazonia, cerca de nuestra Reserva Río Anzu. Este es un evento extraordinario por sí mismo, pero las cámaras trampa en Merazonia los atraparon, dos veces más, en la misma zona general durante los siguientes dos años. Ellos han acumulado cerca de 9000 días-cámara para conseguir estas tres detecciones, así que tienen un promedio de una detección por cada 3000 días-cámara.

Esto es típico de la detección de Zorros Vinagre por cámaras trampa. Los Zorros Vinagre tienen una tasa de detección extremadamente baja, mucho más baja que los jaguares, por ejemplo. En la provincia de Minas Gerais en Brasil, donde los Zorros Vinagre fueron originalmente descubiertos por Lund, se creyó que la especie estaba extinta por décadas, pero una huella fue descubierta en 2005. Esto resultó en un esfuerzo del Fondo Mundial para la Naturaleza (WWF) para fotografiarlo con cámaras trampa, pero tomó siete años de esfuerzo para finalmente fotografiar uno con una cámara trampa. En Costa Rica, en el extremo norte de su área de distribución, un estudio reciente estimó que pudo haber tomado 2500 días-cámara trampa (número de cámaras por día, multiplicado por el número de días que las cámaras estuvieron rodando) para tener una oportunidad 50-50 de fotografiar uno. En un gran parque al sur de Costa Rica, tomó 2376 días-cámara para capturar dos disparos (una detección por cada 1000 días-cámara). En comparación, en el mismo periodo en ese lugar, cerca de 13 imágenes de jaguares fueron realizadas por las mismas cámaras. En los bosques lluviosos de Panamá, en 32000 días-cámara trampa solo se realizaron 11 detecciones de Zorros Vinagre, por una tasa de detección de 1 por cada 3000 días-cámara, la misma tasa de detección que en Merazonia.

Los Zorros Vinagre a menudo viajan en pequeños grupos de no más de 10 animales, y son de las especies de canido más sociales de todas las especies de perros neotropicales nativos. Ellos cazan en su mayoría a grandes roedores del bosque. Tanto machos como hembras colocan marcas de olor en árboles a medida que se mueven a través del bosque. Con el permiso del jefe de Merazonia, Frank Weijand, he alargado el video y lo he reducido a la mitad de la velocidad, de modo que se puede observar la forma en que los tres individuos (presumiblemente dos machos y una hembra), marcan diligentemente el mismo árbol del primer plano. Observe también que un individuo tiene un cuerpo negro mientras los otros tienen pelaje rufo.

VIDEO 02– Video de Zorros Vinagre de Merazonia

Estos perros pesan entre 5 y 8 kg (11-18 libras). Las personas nativas prehispánicas amazónicas aparentemente domesticaron estos Zorros Vinagre antes de la introducción de nuestros perros domésticos comunes. Alfred Russel Wallace describiendo sus observaciones personales de los mamíferos amazónicos en 1889, menciono la presencia de “un perro salvaje, o zorro, de los bosques; caza en grupos pequeños; es fácilmente domesticado, pero es muy escaso”. Esto probablemente se refiere a los Zorros Vinagre ya que es la única especie de cánido nativo amazónico que caza en grupos pequeños. También hay informes de que los Zorros Vinagre podrían haber sido criados con alimento por los indígenas, y tal vez incluso haber sido comercializados con culturas tan lejanas como las islas caribeñas en tiempos precolombinos, aunque la evidencia para esto es poco convincente.

Sin embargo, en los pueblos amazónicos en los que he podido estar (pertenecientes a las culturas Kichwas, Shuar y Huaorani), no he visto ni presenciado ninguna de los Zorros Vinagre domesticados al día de hoy (aunque tampoco pregunté específicamente sobre ellos).

Puede ser difícil para los Zorros Vinagre coexistir con perros domésticos, porque los Zorros Vinagre parecen ser muy sensibles a las enfermedades hospedadas por los perros domésticos. Dadas las grandes poblaciones de perros ferales en varias áreas, incluyendo la cuenca del Rio Anzu, esta es probablemente la única gran amenaza para la supervivencia a largo plazo de los Zorros Vinagre.

Historia evolutiva de los Zorros Vinagre

Durante los días de “isla” no hubo perros en Suramérica (De 70 a 4 millones de años atrás). Los perros llegaron, junto con muchos otros grupos (como osos, tapires, venados, cerdos, camélidos, víboras venenosas, y muchos otros), alrededor de 3-4 millones de años atrás cuando un puente de tierra conectó Norte y Centroamérica a Suramérica.

Los biólogos han asumido por largo tiempo que los perros han diversificado en Norte y Centroamérica antes de la aparición del puente de tierra, y que los múltiples linajes de perros entonces cruzaron el puente de tierra a Suramérica y continuaron diversificándose. Sin embargo, este año (2022) algunos biólogos descubrieron que TODAS las especies de perro suramericanas (Aguará Guazú, Zorro de Orejas Cortas, Zorro Vinagre, Zorro Cangrejero, entre otros) son el resultado de la diversificación local en Suramérica de un único ancestro común que cruzó el puente de tierra ¡hace 3.5 a 4 millones de años atrás! Demuestra la plasticidad evolutiva del genoma del zorro y la velocidad de la evolución.

Estas y otros resultados anteriores también revelan que el pariente más cercano del Zorro Vinagre no es el otro cánido neotropical de bosque Amazonico, el parecido Zorro de Orejas Cortas, sino el Aguará Guazú, un frugivoro de patas largas (Chrysocyon brachyurus) de las sabanas del sur de Suramérica. ¡Las apariencias pueden ser engañosas!

IMG 02 – El Zorro de Orejas Cortas, Atelocynus microtis, es el único perro neotropical de bosque Amazonica lluvioso aparte del Zorro Vinagre. Incluso aunque se parece mucho al Zorro Vinagre; el Aguará Guazú es el pariente más cercano al Zorro Vinagre. !Las apariencias pueden ser engañosas! Fotografía: Igor de le Vinge -Trabajo propio, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=89380067

IMG 03 – El Aguará Guazú, Chrysocyon brachyurus, de las sabanas de Brasil y los países vecinos, es el pariente más cercano al Zorro Vinagre. Fotografía: Sarefo- Trabajo propio, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=718357

Una nota del paleontólogo, zoólogo y arqueólogo danés Peter Lund (1801-1880)

Ademas de descubrir el fósil de Zorro Vinagre (ver la foto arriba), Peter Lund es también el primer que describio cientificamente un Zorro Vinagre vivo, unos pocos años después, pero él no reconoció a los dos animales como el mismo, y estableció el género Icticyon para el Zorro Vinagre vivo. Ya que Speothos fue publicado antes de Icticyon, tiene prioridad por las reglas de nomenclatura científica, así que usamos ese nombre en lugar de Icticyon.

IMG 04 – Creo que esta es la primera pintura de un Zorro Vinagre. Fue hecha por Peter Andreas Brandt en Lagao Santa, Minas Gerais, Brasil, donde el estaba participando como el ilustrador científico para Peter Lund. Lund descubrió el primer fòsil de Zorro Vinagre y, poco después, el primer Zorro Vinagre vivo. Talvez estos individuos pintados fueron los mismos que utilizó Lund para su descripción científica del animal vivo.

Lund también descubrió fósiles de un perro más grande y robusto, Speothos pacivorus. ¡Este poderoso animal se extinguió solo hace 11000-12000 años! La Amazonía debió haber sido un lugar peligroso para los humanos cuando estos animales estaban cerca.

IMG 05 – Una especie de Zorro Vinagre extinta, Speothos pacivorus, era un animal fuerte y de pesada complexión. Se extinguió solo hace 11000-12000 años atrás. Crédito de la fotografía; https://prehistoria.fandom.com/es/wiki/Speothos_pacivorus

Lund pasó varios años excavando las cuevas de Minas Gerais. Aparte de los Zorros Vinagre, también descubrió el famoso Tigre Dientes de Sable en estas cuevas, así como restos humanos. Él fue el primer científico en descubrir que los humanos vivieron junto a estos animales extintos. En esa época, las grandes autoridades a nivel mundial, como Cuvier, creían en “catástrofes” que eliminaban todas las especies de una época, después de las cuales el mundo era repoblado por la creación de una nueva fauna. Esta creencia es probablemente lo que evitó que Lund se diera cuenta de que su fósil de Zorro Vinagre Spaethos venaticus y su Zorro Vinagre Icticyon eran la misma especie. Pero eventualmente sus descubrimientos comenzaron a erosionar sus creencias científicas (y religiosas). Profundamente en contrariado, estaba confundido pero confiado de sus conclusiones sobre la coexistencia de humanos y animales extintos. Le escribió una carta a un amigo:

“Por otra parte, no puedo negar que los aspectos de los puntos previos, los cuales creí haber establecido, han sido cubiertos por una nueva oscuridad, y lo que pienso ha sido clarificado no ha sido completamente iluminado. Esto se refiere, por ejemplo, al… tema importante concerniente a las circunstancias de la sucesión de las eras y la identificación de especies, y la cuestión no menos importante de la línea de separación entre ellas. Esto último se volvió para mí totalmente oscuro. Observo varias especies extintas, como las que descubrí por debajo de esa línea hacia el presente, y varias de las especies del presente se mueven sobre ella hacia el pasado. … Este año fui afortunado de encontrar restos [humanos] bajo diferentes condiciones, lo cual no me deja duda sobre que ellos han sido testigos del fin de al menos cinco especies de mamíferos.” – Peter Lund, como se tradujo del portugués por Google Translate, con algunas “correcciones” (espero) de mi parte.

Lund estaba tan conflictuado por sus descubrimientos que el nunca regreso a sus cuevas. La historia es analizada (en portugués) por Pedro Ernesto De Luna Filho (2007), Peter Wilhelm Lund: Sus investigaciones científicas y la razón por la que repentinamente detuvo su investigación.

La carta superior (en su original portugués) fue tomada del artículo de la tesis de De Luna. Me gustaría saber portugués, aunque el español es casi lo suficientemente bueno para entenderlo.

IMG 06 – El vecindario de Lund en Lagao Santa, Brasil, pintado por Peter Brandt alrededor de 1840. Lund vivió en Brasil hasta su muerte

Lou Jost, Fundación EcoMinga

Traducción: Salomé Solórzano-Flores